It's been really windy lately. I notice that I get anxious in high wind, imagining how it is sucking the moisture out of the already dry landscape. I notice worry that the wind will topple a tree. Indeed the oak across the street just fell so my worry finds reason and grows stronger. I see how my mind gets caught up in imagining how if there were a fire right now, this wind would turn it into a fire storm. My thoughts travel into the past remembering all the times the wind has beaten against the house like this, causing any present discomfort to be compounded. My thoughts travel into the future, wondering whether with global warming, this hard wind will become stronger. Images from newscasts of the devastation caused by tornadoes in the midsection of the US rise up to remind me of the impermanent nature of these structures we call home.

I notice too how with the wind blowing so hard, everything else going on in my thoughts and emotions is tinged with my distressed reaction. Something that wouldn't normally bother me now causes aggravation because I am already a little on edge.

This clear noticing of what is really happening in my experience is not to whine about the wind, or to judge myself for making a mountain out of a molehill, but to compassionately notice how the mind takes me on an unskillful journey away from this moment, how it spreads misery in its wake and compounds the potential for suffering. The noticing and compassion are skillful, and as I focus I feel the tension in my body releasing. This is the practice of mindfulness.

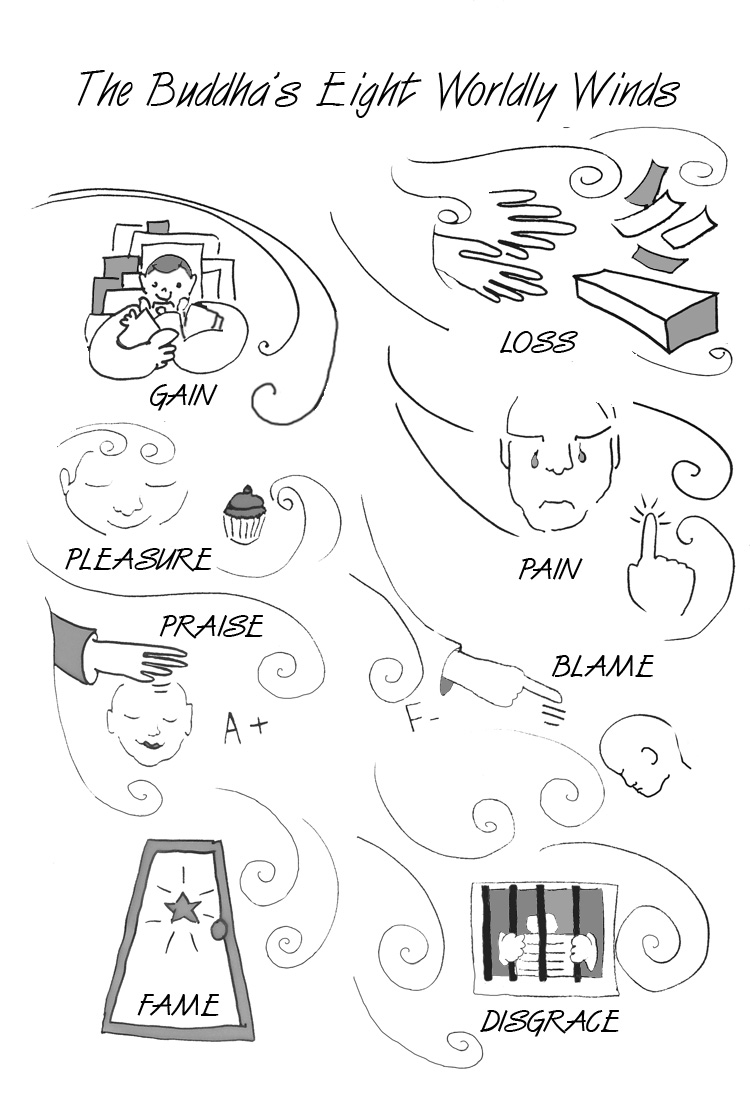

The Buddha created a whole set of teachings based on the changeable nature of wind. The Eight Worldly Winds* is a set of eight paired experiences -- pleasure & pain; gain & loss; praise & blame; fame & disgrace. Like the wind they arise and fall away, then arise again and fall away again. All of life experience is like this.

I notice too how with the wind blowing so hard, everything else going on in my thoughts and emotions is tinged with my distressed reaction. Something that wouldn't normally bother me now causes aggravation because I am already a little on edge.

This clear noticing of what is really happening in my experience is not to whine about the wind, or to judge myself for making a mountain out of a molehill, but to compassionately notice how the mind takes me on an unskillful journey away from this moment, how it spreads misery in its wake and compounds the potential for suffering. The noticing and compassion are skillful, and as I focus I feel the tension in my body releasing. This is the practice of mindfulness.

The Buddha created a whole set of teachings based on the changeable nature of wind. The Eight Worldly Winds* is a set of eight paired experiences -- pleasure & pain; gain & loss; praise & blame; fame & disgrace. Like the wind they arise and fall away, then arise again and fall away again. All of life experience is like this.

Here is a drawing I did of the Eight Worldly Winds.

Now let's look at them one by one.

Now let's look at them one by one.

We seek out pleasure, and don’t want it to end so we cling to it. Why would we not?

Here’s one reason: When we are afraid it will end, we are not really in a state of enjoyment. Instead we are caught up in the suffering of grasping and clinging. The only way we can truly enjoy pleasure is to let go of the fear of losing it. If we allow it to come and allow it to go, the way we might enjoy spending time with a butterfly who has alighted on our extended palm, we savor the moment. We know it is fleeting.

We recognize that while we may have the power to capture the butterfly and keep it, if we did so the butterfly would no longer be what it is, would no longer be able to give us the pleasure of seeing it flit and fly from flower to flower. To keep it, we would have to kill it. If we did so, we could still admire the colors, shapes and details of the wings, but the essence of what makes it a butterfly is gone.

In this same way we can notice how pleasure disappears if we hold on too tight, wishing it would go on and on.

We recognize that while we may have the power to capture the butterfly and keep it, if we did so the butterfly would no longer be what it is, would no longer be able to give us the pleasure of seeing it flit and fly from flower to flower. To keep it, we would have to kill it. If we did so, we could still admire the colors, shapes and details of the wings, but the essence of what makes it a butterfly is gone.

In this same way we can notice how pleasure disappears if we hold on too tight, wishing it would go on and on.

We dread pain. Why would we not?

Here’s one reason: When we have a pain and get caught up in how much we don’t want to be in pain, we compound it with self-inflicted suffering. When we are able to fully be present with pain, we can see how it becomes a series of physical sensations that change constantly, diminish over time and eventually pass away.

One of my granddaughters who is an adult now was terrified of bees when she was little. She wasn't allergic to them but she was still afraid of being stung, so she refused to go out in our garden. I sat with her and asked her, ‘What are you afraid will happen?’

‘I’m afraid a bee will sting me.’

‘And if a bee did sting you, then what would happen?’

‘It would hurt.’

‘Have you ever been hurt before?’

'Yes.'

'And what happened when you were hurt?'

‘I cried.’

‘And then what happened?’

‘The hurt stopped after a little bit and I stop crying.’

‘And then what did you do?’

‘I went and played.’

And with that statement she smiled at me with the light of recognition. Then she hopped off my lap and went straight outside to run around the garden with great joy and abandon.

We can do this for ourselves as well. We can come into skillful relationship with the Worldly Wind of pain, and not let the fear of it rule us. We use common sense, but we don’t stop living just to avoid pain, because that state of avoidance is ongoing pain.

It’s one of the ways we create dukkha, the chronic suffering that comes from our grasping at, clinging to and pushing away these Worldly Winds.

We like to gain a new friend, strength, ability, knowledge, health and wealth, and we are determined to hold on to what we've got. Why would we not?

Here's one reason: While opening to the wealth of the world is a delight and there is maintenance required, when we cling to a it we strangle it, whether it's a friendship or strength, ability, knowledge, health or wealth. When we experience the naturally occurring changes of life, we suffer much worse than simple disappointment. We fall into a sense of diminishment that sucks the joy out of every moment spent with the gains we have made.

We fear loss of loved ones, of health, wealth, strength, ability and anything else we value. Why would we not?

Here’s one reason: We create an ongoing state of suffering that precedes the loss. When the loss occurs, as it will, we can't be present for the experience because we are still struggling, trapped under all the layers of fear we have created. If we can't bring ourselves to be present with the loss, then how will we ever recover from it?

As women of a certain age, my students and I have all lost some of the people who mattered most to us in the world. So we know about loss. This knowing informs us. We would never wish for it or wish it on anyone, and yet when we are present with the loss itself, when we feel the physical and emotional impact of loss in each moment, we notice how it shifts and changes, arises and falls away. This noticing makes us wiser and more resilient. It carves within us the capacity to hold more love and deeper compassion.

We enjoy praise so we do things to earn it. Why would we not?

Here’s one reason: Chasing praise from another person throws us out of balance. We can’t be grounded or authentic if we are second-guessing what someone else would like us to be. Ironically, we can't hear the praise when if it comes because we are caught up in our hopes, fears and expectations.

As women we may be more prone to make choices in order to get praise. Our feelings may be hurt if our mate doesn't compliment a meal we cooked. And heads up to husbands: silence is often interpreted as criticism.

Of course we want whoever eats what we cook to enjoy it. But can we live enough in the present moment to arrive at the dinner table having so thoroughly enjoyed the process of cooking that we are not hankering after praise? Can we be so present with the experience of eating the meal, and with the pleasure of the company, that we are not waiting to hear ‘Wow, you are the greatest cook on the planet!’? Expectation sours our own enjoyment. We can't taste a thing.

We so dread blame that we’re careful to do everything we should and nothing we shouldn't. Why would we not?

Here's one reason: While it is wise to lead a blameless life by living with integrity, honesty and kindness, sometimes we fail. In a moment of oblivion or distress, we do something that causes harm.

If we are tied up in knots of fear of being blamed, we will be more likely to do something unskillful, since our intention is not aligned with being present and being compassionate, but with some future scolding we might receive.

When blame falls on us can we be skillful in how we deal with it? Can we acknowledge our error or misjudgment? And if the blame is unjustified, can we see it as simply an error and not an indictment of us?

We crave recognition, maybe even fame. Why would we not?

Here’s one reason: Because the longing for recognition drags us out of the present moment. We live in our minds in some future moment when we will receive the recognition we so deserve. If that moment ever comes, we won't have the practiced skill of being present in order to notice it. We will be craving greater and greater recognition.

Even if we don't relate to the word 'fame', we each have our reputation. Among our family, friends and work associates we become known for certain qualities, traits and behaviors. While praise is a one-time thing, reputation is cumulative, and colors how we are perceived for years to come.

We want to avoid disgrace. Why wouldn't we?

Well here’s one reason. Disgrace can become such a terrifying outcome that people in certain cultures would rather die than be disgraced. But even if that is not the case, allowing the shadow of potential disgrace to loom over us can really throw us out of balance, blind us to the rest of what is going on in the present moment.

If we live mindfully, aware of our connection with all life, aware of the impact our choices have on ourselves, those around us and the world, while we will not be impervious to failure or error, we will be more likely to have the wisdom to know how to make amends and assure we don't make that particular mistake again. We can recognize the universal nature of this and all the Eight Worldly Winds.

If we live mindfully, aware of our connection with all life, aware of the impact our choices have on ourselves, those around us and the world, while we will not be impervious to failure or error, we will be more likely to have the wisdom to know how to make amends and assure we don't make that particular mistake again. We can recognize the universal nature of this and all the Eight Worldly Winds.

Our feelings around reputation can extend beyond ourselves. One student pointed out that if we identify with groups -- a favorite team, a political party, a country -- we feel connected and affected by their triumphs and stardom as well as their failures and disgrace.

With our previous exploration we can see how we might, through awareness, temper the effect of these Eight Worldly Winds. If notice them, we notice that they pass.

If we note ‘pleasant’ or ‘unpleasant’ for any experience, we strengthen our ability to see clearly the strong lure to get caught up in a story about the pleasant or unpleasant experience, and the emotions that are ready to rise up to further entangle us in associated memories, planning, worry, regret, daydreaming, etc.

At any moment during this entanglement of the mind, we can recognize it, and reset our intention to be present rather than lost in the past or future. When we do this, we begin to see the nature of what is. If we see in this moment one of the Eight Worldly Winds arising, and we stay present to observe it, we will see that it is insubstantial. Under observation it breaks down into component parts. We can see the desire or the fear underlying it.

Recognizing the underlying longing or fear, we can be compassionate with ourselves, and that quality of kindness offers a release from the attachment to the Worldly Wind. As we stay present, we see that the worldly wind changes over time. It is impermanent. It arises and falls away. We can simply be aware of this big wind passing through our field of experience.

If we can open our view wide enough to see the nature of how they arise and fall away again and again, we can find ease in simply being alive and present to experience it all.

Remember the story of the farmer who lost his horse? It applies very well here, so I’ll tell it again.

A farmer’s horse got loose from the corral and disappeared. The farmer’s neighbor said, 'What a calamity! How will you plow your fields without your horse?' A few days later the horse returned with six wild horses in tow. Wow! Now the neighbor said, 'That's fantastic! What great luck!'Then the farmer’s son fell off the horse while trying to tame it, and he broke his leg. 'How terrible!' the neighbor sympathized. The next week the army came and took all able-bodied young men, but not the son hobbling around on crutches. The neighbor could not believe the farmer’s good fortune. At every turn the neighbor reacted as if tossed around on the winds of fortune. But each time, whether the neighbor commiserated or congratulated, the farmer simply said he didn't know whether this was good or bad fortune. Maybe yes, maybe no. He couldn't say.The farmer was wise. He recognized that none of us know the outcome of any given event, that all things and all experiences are insubstantial, impermanent, and beyond our control. He recognized the nature of the Eight Worldly Winds.

In moments of clarity, when we are fully present, we recognize this as well. We can simply be present with the experience as it arises and falls away. Arises and falls away...

* 'Eight Worldly Winds' is one translation. Others are 'Eight Worldly Dharmas', and 'The Failings of the World'. This is from the Lokavipatti Sutta of the Pali Canon, the earliest scriptures of the Buddha’s teachings, which had been passed down orally from generation to generation of monks for 500 years until in 1 BCE, they were committed to writing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your thoughts on what you just read. Does it have meaning for you? Does this subject bring up questions?

I am aware that sometimes there are problems with posting comments, and I would suggest you copy your comment, don't preview it, just 'publish'. That way if it gets lost you still have your comment to 'paste' and resubmit. Sorry for any inconvenience and I hope it doesn't discourage you from commenting!